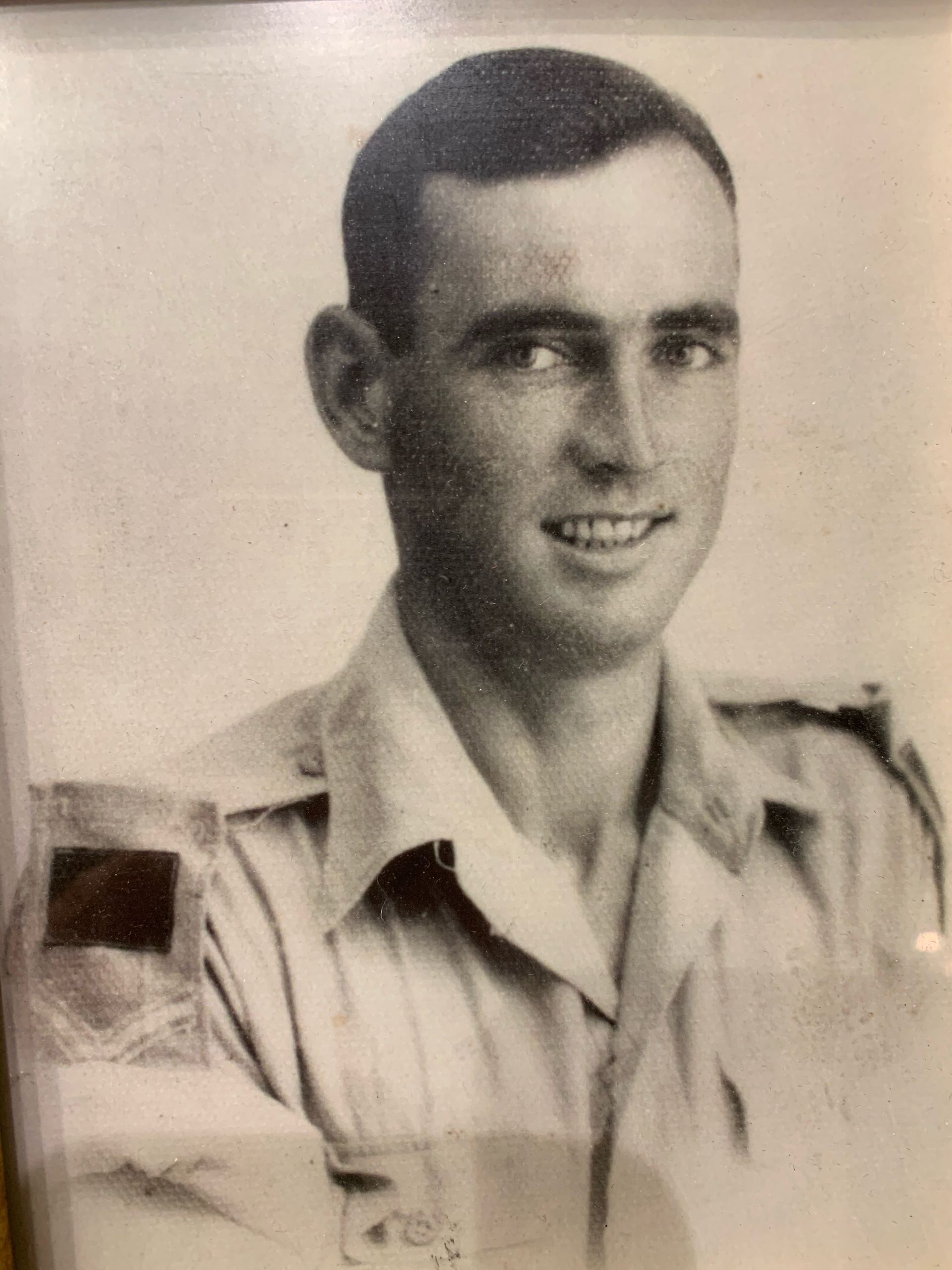

Life for my father, Alexander Joseph Gillis, was not a walk in the park but it was a wonderful gift. His frequently reiterated family stories, which he told to his 5 children on Sunday afternoons amid melodic riffs from a long playing record, helped create my understanding of dad’s world. The way he proudly told it, his family was a hard working group who were “directly” descended from Scotland’s Bonnie Prince Charlie. I never saw him wear a kilt but I do remember him (maybe too often) raising a glass and saying Slainte – Scottish for “cheers”!

My father or AJ as his closest friends called him, was a child born in World War I and a man developed during World War II. Born in February of 1918 in Nova Scotia, Canada he had three sisters and two brothers who shared a home on the family farm on the banks of the fish rich Margaree River in Cape Breton. The Gillis name is a common one in the area and particularly in SW Margaree. Many of the male Gillises shared first names. This made for a challenge when hearing local gossip. Just what Gillis was being talked about? The answer was a three part name. The first was your grandfather’s name followed by your father’s first name and ended with your own given name. Take my brother Hugh for example. His grandfather was Hugh, his dad was Sandy (Alexander) and his own first name was Hugh. When we visited my father’s birthplace my brother was introduced as Hughie Sandy Hughie leaving no doubt as to his lineage!

My dad attended high school and according to his military records he left school at 15 after completing grade 10. At the time the job opportunities for young men in Cape Breton were mainly restricted to coal mining, farming and laboring. My father was rather vague about his early work history but he alluded to working on the family farm, and driving trucks. Unquestionably in 1939 when dad was was 21 years old there was uncertainty in the world and instability in the Nova Scotia job market. In that year as war was declared AJ decided to ride the rails to look for work. He ended up in Canmore Alberta.

I am uncertain how long Dad spent in the Canmore region but he did find work with Imperial Oil for $30 a week! On December 13, 1939 he enlisted in the Canadian army and sailed to Europe on the SS Duchess of York in September 1940. My dad must have shared some of this story with me when I was a young girl because somehow I committed his regimental number to memory. M- eleven – fifty five is how he pronounced it. I had the occasion about five years ago to speak with a distinguished and high ranking veteran of that last world war and told him my father’s number. Without hesitation he said “That number tells me exactly where he signed up. Canmore” he declared.

AJ’s first deployment was to North Africa. That campaign lasted from June 10, 1940 to May 13, 1943. The offensive was a “struggle for control of the Suez Canal and access to oil from the Middle East and raw materials from Asia.” It seems dad was there for much of the operation and while engaging in combat he managed to contract malaria, a disease that was to recur intermittently during the remainder of his life.

Before the North African operation ended Dad was transferred to the Italian campaign. There he fought in one of the war’s toughest battles – The Battle of Ortona. Canadian troops were deployed to the little Italian town and engaged in hand to hand combat with German soldiers. The Canadian War Museum in Ottawa has an excellent and explicit exhibit that brings to life the reality of the rubble covered streets and hidden land mines that the brave Canadians encountered as they dodged machine gun fire and maneuvered between booby trapped houses. The sounds and smells the exhibit mimicked are a poignant lesson in the realties of military action.

On VE Day my dad was in a military hospital in England recovering from an injury he had sustained. He told the story of hearing the news of the victory in his hospital bed. The fellow soldier next to him had serious leg wounds and could not walk. AJ’s trauma resulted in an arm encased at right angles leaving only one workable limb. With his single good arm he managed to hoist his “roommate” into a wheel chair and pushed him out to the local raucous celebrations.

One final anecdote that my father told me and my brothers and sisters went like this. “Kids, I was promoted 13 times and demoted 14!” It made us laugh. I guess that was his way of protecting us from facing the harsh realities of war.

Father never boasted about his medals and awards. What our family did discover through Canadian military records after his death was that dad was “mentioned in dispatches”. This is a highly regarded recognition from the King for “gallantry and distinguished service.” Well done dad!

These were about the only stories my siblings and I ever managed to rip from AJ’s memory. When we asked more explicit questions like “Did you have to kill anyone, daddy?” we were met with elusive answers. My sense is that the deeply hurtful aftermath of combat and his fatherly protective sense kept him from voicing his personal emotional damage.

Now my dad was no saint. In fact, far from it. He had his demons that I suspect arose in part from those 7 years in military service. And to assuage those demons he would often self medicate with alcohol. So in that way, life was no walk in the park.

On the other hand, my father raised us with an incredible reverence for music, poetry and sense of duty and community. He considered himself lucky to have survived the war and to have seen his children grow and live safely and productively. So in that way his life was a wonderful gift.

On this November 11, 2020, amid all the unbelievable challenges we have recently shared across the world – let us remember the brave men and women who served in our terrible wars. Let us salute the courageous people who have given up years of their lives for country and for humankind.

And to:

My dad

M Eleven 55

Slainte!!

Sassy Blog